In this article–targeted to retrospective facilitators–I describe my experience going from a simple retrospective format to a more structured one following Derby and Larsen’s book on Agile Retrospectives.

I’ve seen the first format working for teams of 2/3 developers new to retrospectives but it was ineffective for larger teams on challenging projects–it ended up feeling like a status update meeting–so I introduced to the second format.

I start by describing what I call a classic retrospective and the biggest risk I encountered with it. Then I describe the structured retrospective I introduced. Finally some tradeoffs of the structured retrospective.

I gave a 15 minutes talk about this subject at Pivotal Labs in Los Angeles, you can watch it here. If you’re interested I wrote a blog post about measuring retrospective success.

This article is about retrospective for co-located teams.

The classic retrospective

If you’re practicing a retrospective it’s very likely that this is the format you’re using.

The whole team gets in a room.

Then a random person is picked as the facilitator to ensure the conversations are kept on track and timeboxed.

Then the whole group starts adding last iteration events to a whiteboard–or an electronic equivalent–with three columns:

- mad

- sad

- glad

representing the feeling that the event triggered for that person. Multiple variations of this exists–ie. start, stop, continue–but the root activity stays the same.

After the team is done adding items the facilitator kicks off the retrospective by reviewing the outcome of the last retrospective and then starting timeboxed discussions about each event on the board.

The facilitator is also asking if there is any “action item” to make that event better. In this retrospective format an action item is often described as an attempt to prevent a negative event from reoccurring.

Sometime the scrum master act as the facilitator. In my experience is very unlikely that the team will recognize the same person pressing for delivery and deadlines as an unbiased facilitator. The result will be that the retrospective will feel just like a status update meeting.

Pro of this retro

- It’s really simple to explain to people new to retrospectives because the format is always the same

- Everybody’s event is very likely to be–perhaps briefly–discussed

- The facilitator can be a random team member and doesn’t need any special training (not quite true but more on this …)

Cons of this retro

- A randomly picked facilitator might not have the skills,empathy or willingness to manage arguments. In extreme cases I’ve seen that person hijack the retrospective making it about a subject of his/her interest.

- Using the same format for months won’t keep people’s brain engaged. It’s the responsibility of a diligent facilitator to do that.

- The mad, sad, glad–or whatever names you use–is an effective way to collect events but can’t generate insight of the overarching problems that generates them.

The biggest risk is…

focusing on each event and missing an opportunity to see the overarching root cause.

This is an example based on a real project I was on: a sad face on “slow deployment” and someone starts talking about “how deployments take over a long time and that’s really slow yada yada yada” so someone comes up with an “action item” to “investigate deployment speed”.

Then a meh item is “integration with the BAM API is unreliable” and someone talks about “how 3 out of 5 times BAM is down” and so someone comes with another “action item” to “use circuit breaker pattern to tackle BAM unavailability”.

These “action items” seem adequate solutions to each problem but by attempting to individually fix them we obfuscate a possible overarching issue and might miss the root cause that would affect them both.

In this example the overarching problem–unveiled by the structured retrospective I’ll introduce next–was miscommunication with the BAM team which was also sharing the responsibility of dev-ops deployments. Later in the article I’ll describe the experiment we attempted to fix that.

So what’s the alternative?

A quick fix would be introducing pattern matching. After the board is filled up the whole team works towards grouping the events. But what about the multiple action items? And the rotating facilitator?

Let’s be clear: it’s critical for the facilitator to be skilled or willing to learn and experiment. Facilitation is a very hard job and it’s too often dismissed. Ideally the facilitator is external to the team so it doesn’t have a stake in the project.

Have you tried to borrow a facilitator from another team?

The facilitator should try a structured retrospective. For the sake of this article’s clarity I use the word structured to distinguish it from the mad,sad,glad + action item that I’ll call “classic retrospective”.

A structured retrospective is divided in 5 parts:

- setting the stage (5 minutes)

- gather data (20 minutes)

- generate insight (15 minutes)

- plan an experiment (10 minutes)

- close up (10 minutes)

I divided the activities so the retrospective would last 60 minutes. I suggest you schedule it for 75 minutes for padding between activities. If you have iterations longer then one week you might need more time. It’s very unlikely that you can achieve an effective retrospective in less then one hour I used a visual timer so the group can see how much time is left.

One of the major differences from the “classic retrospective” is the plan an experiment part focused on one experiment rather then a series of “action items”.

People accustomed to the classic version want to focus the retrospective on their topic so explain that that might not happen and that instead the team will focus on what has higher priority for the group.

This might upset someone using retrospectives to vent their feelings. Make sure that there is still a place for them to do that perhaps before the retrospective.

As the facilitator have you asked your team what will achieve value for time invested in this retrospective?

As the facilitator have you asked your team what have we tried before? what happened? what would you like to happen differently?

Make sure the retrospective objective is defined by the team.

Setting the stage

Asking those two questions is a good way to set the stage and make sure everybody understands the purpose of the retrospective. One of my favourites exercise is to read Kerth’s prime directive:

Regardless of what we discover, we understand and truly believe that everyone did the best job they could, given what they knew at the time, their skills and abilities, the resources available, and the situation at hand.

ask for a verbal yes from each member. If there are individuals not willing to set aside opinions–at least for the sake of the retrospective–then you have a bigger problem and you should cancel the retrospective. There might be someone in the room that people don’t feel comfortable around or other group dynamics that need investigation. Have one on one conversations with those individuals that didn’t agree with the directive and investigate what their opinion is.

The retrospective should be a no naming no blaming activity and the prime directive is a strong and meaningful sentence that encapsulates those values.

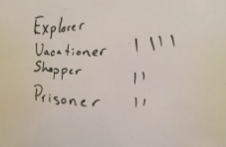

Explorer, Shopper, Vacationer, Prisoner

A good activity to discover–or track–team interest about the retrospective is ESVP. You will anonymously collect how the participants feel about the retrospective.

At one end the explorer wanting to leave no stone unturned and enthusiastically learn as much as possible. At the opposite end the prisoner that was forced in to the retrospective.

If you have a room full of prisoners you should consider cancel the retrospective. Having occasional prisoners is ok–make sure you acknoledge their presence and thank them for their patience and participation.

Do not ask who’s the prisoner if they feel like speaking up they will.

In one retrospective I facilitated I had some prisoners. I eventually learned–during the closeout step–that the time of the retro was too close to the end of day forcing them to rush catching their train back home.

Make sure you comunicate to the group how long the retrospective will last and commit to end on time.

Gather data

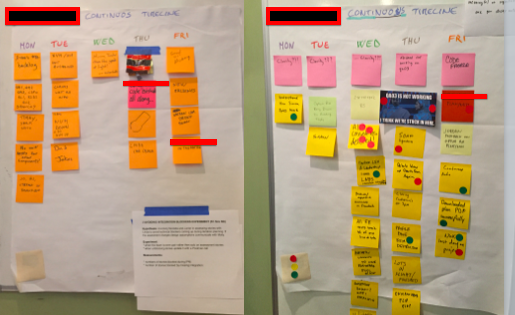

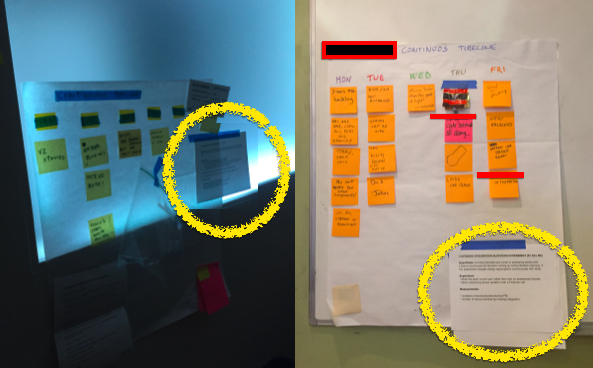

I asked the team to collect data during the week on a continuous timeline so during retrospective they could read that and remember what happened during that iteration–add new things if they forgot–ask each other questions and be ready for the next step.

It’s important for the whole team to read and understand what’s on the board.

Some of those events can be color coded at the time of the writing or you can decide to color code during the retrospective. The second option might spark interesting conversations because an event–ie. quick and dirty refactoring–that is sad from the eyes of the author could be a happy for others.

Other good pieces of data to show at this point are number of delivered stories/points, number of deployments, bug count.

The timeline should collect events–and hard data–for example: “spent 16 hours fixing the dropdown bug” instead of “we don’t deliver fast enough” which is a personal consideration. Personal consideration and feeling are important and they will be discussed in the next step: generate insight.

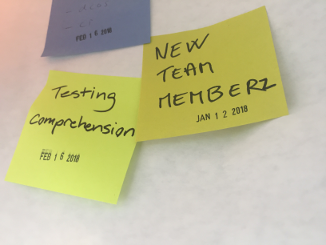

Suggestion: If you’re keeping the post-its from the weekly continuous timeline for a longer project retrospective I found it useful to timestamp the iteration week to facilitate the creation of the project timeline:

Generate insight

Once we have information about what happened on the last iteration the team can start looking for patterns. Ask them to move the events in to groups/topics. As a facilitator make sure the whole team participate.

You should now be halfway trough your restrospective and have a handful of overarching topics. Ask the team to vote on each group so the one with highest count will be the focus of the experiment.

It doesn’t always work

If the group is large or the team has a lot of friction it might be hard to decide a topic to discuss within the time allocated for retro. In that case is good to prepare a list of topics to generate insight on. I like to ask those to individual team members before the retro.

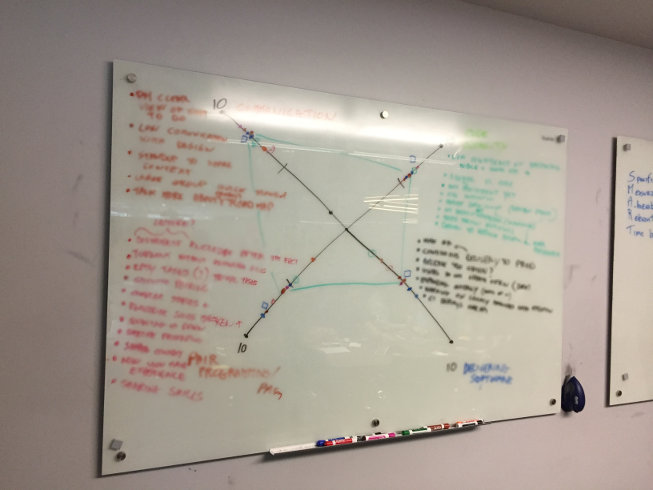

During team radar people vote from 0 to 10 how well the team perform on a number of topics. Then the conversation starts and the facilitator add notes as people talk about the reason for their votes. This is a direct way to generate insights on specific areas/topics.

Experiment

Once one ovearching topic has been identified it’s time to formalize a measurable experiment to incorporate in the next iteration. I like to stick it to the timeline so everyone can read it.

I like the experiment to have the following format:

- Hypotesis: “a supposition or proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation”.

- Experiment: “a procedure undertaken to test a hypothesis”

- Measurement: having measurements help determine if the experiment was successful or not

example one:

- Hypotesis: Having two BAM API developers pairing–ideally on site–with the team will help speed up deployments and debug BAM problems.

- Experiment: Propose to the BAM team manager to have two devs to work next to the team. If not possible use remote desktop sharing with webcams to see each other.

- Measurement: Count number of times BAM is not operational. How long it takes for BAM to be operational again. How many times BAM developers are pairing on site. How many times BAM developers are pairing remotely.

example two:

- Hypotesis: The team agrees that: 9’oclock is an acceptable standup time and starting standup everyday at the same time regardless of who’s missing.

- Experiment: Standup starts at 9am everyday with a–weekly–facilitator assigned on the calendar. If the measurement shows low presence reschedule standup at 9.30am. Enrico will create the facilitator calendar for the next 2 months.

- Measurement: How many times standup starts after 9? How many people are missing the 9’oclock standup.

Closing

Now is the time to finish the retrospective and there are two activities I like.

One is to end on a high note with the apreciation activity. This activity is only for praises. For example: I apreciate Linda for her hard work commuting everyday to be onsite. or I apreciate David for his honest feedback while discussing code.

There will be akward silence.

Remind everyone to think back the whole iteration and that even small things should be brough out.

I facilitate a team where people were offsite and unable to attend the retrospective so I suggested to write the apreciation on a piece of paper and let the product owner delier that once back at the office.

Another activity is to get retrospective feedback from the group. I’d start with anonymous feedback. This is a great way to make sure you and the group are on the same page.

Cons of a structured retrospective

I was told this retrospective format feels like you’re working. It’s true. The facilitator needs to prepare activities and collect data and the group will need to be much more engaged and will feel like they’re working rather then sitting in a status meeting. I think this is good but be prepared.

If you don’t have a willing facilitator it’s hard to introduce this retrospective format.

In small teams of 2/3 individuals this format is not very effective. I tried and the folks didn’t see an advantage over the classic format.

The activities are made for face to face interactions and are much harder–sometime inadeguate–to run with remote folks. With a remote team try run the structured retrospective when the team meets face to face.

Conclusion

If your classic retrospective feels like a status meeting I hope you will switch to a structured one and pick some new activities from this article and Derby&Larsen book.

I’d love to hear your experiences and challenges switching from a classic to structured retro in the comments. If you’d rather start a 1:1 conversation feel free to private message me on twitter @agenteo.